by Stephen Threlkeld

In memory of Stephen Threlkeld some of his trip reports will be reprinted in 2014. This one originally appeared in the Summer 1991 issue of Qayaq.

To arrive at Fred Binding’s cottage after weeks of winter in the city is literally to be transformed. The cottage is on the very edge of Georgian Bay, about half way up the east side of the Bruce, a little above Lion’s Head, on a cliff top overlooking the Bay. The fixed hexagonal table and benches in front of the cottage seem to stick out over the top of the cliff by about half a metre. Beneath them it is a sheer drop of about 30 metres to the water be-low. When we arrived on Friday evening (April 26) the water was like a sheet of glass with the surface broken only by two pairs of mergansers, their head feathers looking like Dagwood’s hair. It was cool enough for the great wood fire in the living room to be appreciated.

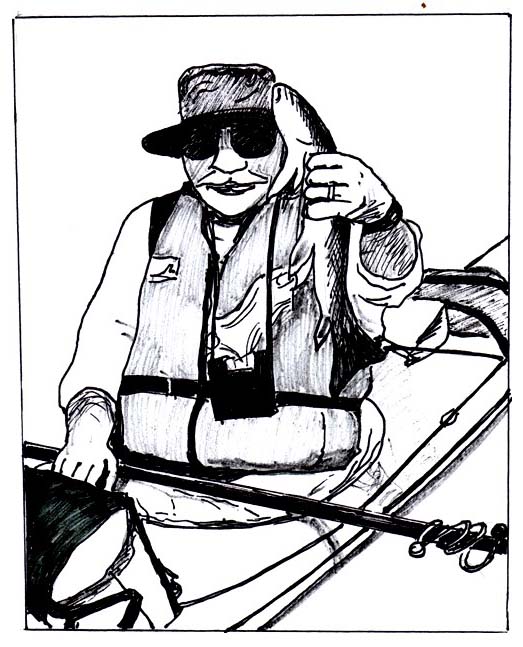

Next morning the water was still calm, lazily flat and inviting. We drove to the government wharf at Dyer’s Bay and met the others, Jim Coles, Stewart McIlwraith, Doug Cunningham, and Vic Thompson. Fred soon had us organised. Two were to go south along Dyer’s Bay, two were to go north. Mark Taylor and I were to put in at Cabot Head and paddle towards Tobermory, and Fred was to take a further section nearer Tobermory.

I should explain that the red-necked grebe appear to be changing their migratory habits and early in the year may be seen in greater numbers in Georgian Bay. Provincial government officials are anxious to get counts of the grebe, hence GLSKA to the fore. The hunt, Virginia, is to establish a count and not to shoot the grebe. The red-necked grebe, an uncommon grebe, winters on the east coast south to Florida, generally in salt water. They spend their summers mostly on ponds and lakes in western Canada and north to Alaska. Their migratory path from the east coast is mainly across the United States with Georgian Bay the northern limit of the path in our area. They are also found on the Pacific coast where they winter.

And so to Cabot Head. A gravel, use-at-your-own-risk, road took us there. Cabot Head is the site of a functioning lighthouse, and, we observed, fog-horn. It was down the many steps of the steep cliff before we put in off a stony shore to head west, not north. From Cabot Head to Tobermory the coast runs almost due east and west, in fact exactly east and west by compass with variation not taken into account.

Paddling a few hundred metres, we came to the entrance of Wingfield Basin. Navigational aids at the far end of the basin were evidence of its usefulness as a haven to small craft caught in inclement weather. Lining up the two lighted mast-like aids, one behind the other, provides a position line of 182 degrees to direct craft into the basin. We paddled into the basin, a small beautiful, practically deserted, quiet bay with a few loons and buffleheads. Later, someone said the basin may become a public campground – I hope not.

Mark Taylor, unlike myself a lab biologist, is a real biologist, a field biologist. I am always impressed by the powers of observation of good field biologists, and it wasn’t long before Mark spotted some unusual activity in a small stream at the far end of the basin. We paddled over. Mark got out to take a look. I sat lazily in my kayak soaking up the sun, the fresh air and the peace of it all, and then Mark appeared holding a 70 cm fish, a sucker.

On from Wingfield Basin we paddled along the coast with clear water and sunny skies. The next thing we saw, again thanks to Mark (I must really start using my eyes.), was a mass of loons rafted up, about 200, a kilometre or so out into the lake. Then it was time for lunch, on the rocky shore.

Later in the afternoon, no red-necked grebes yet, but one of the most spectacular sights of a spectacular trip, a couple of horned grebes. Look up your bird book, and you will see how spectacular they are, with orange flashes on each side of their head. They were quite close and the light was perfect for viewing them. No Virginia, they do not have horns like a bull moose.

As we travelled west we noticed strange shapes on the horizon. Cliffs of strange islands? Mysterious palisades rising out of the water? A new weather phenomenon? Perhaps a series of water spouts heading towards us, or just odd clouds? We believe they were mirages of some sort.

We were moving west at a fair pace when it occurred to us that our speed had more to do with a freshening wind out of the east than with paddling technique. We decided to return to Cabot Head. A different story. The wind had freshened considerably, and although the spray and the waves washing over the bow were refreshing, it was hard work for an hour or so, with not much chance for a rest. And then, as we once again approached Wingfield Basin the initial calmness of the day was restored. We turned into the basin, inspected a burnt out barge, and then landed on the sandy beach of the inner shore of the basin, where I, due no doubt to a certain stiffness from sitting for a while, on getting out of the kayak staggered for a dozen metres and fell on my back on the sand in the sun. A surprisingly relaxing feeling. No Virginia, there’s no alcohol on GLSKA trips!

Once again we looked at the spawning suckers. A little way from the suckers, sunning themselves, and doubtless contemplating a special meal, were a dozen or more turkey vultures. The occasional loon, bufflehead and merganser were still around. We left Wingfield Basin happy, with a beautiful trip behind us, and lugged our kayaks up the steps of Cabot Head. Altogether we think we travelled about 15 kilometres. Did we see any red-necked grebes? No. But wait, the day was not over.

On the way back, down the use-at-your-own-risk coast road, Mark who was in front stopped his car, and brandishing his field-glasses called to me to take a look. And there it was, out on the calm waters of the lake, one red-necked grebe. So far as I know it was the only one seen by any of the participants of either this year’s hunt or last year’s.

The day was still not over, not before we had dinner at the Big Tub Lodge in Tobermory. The lodge had changed little (I swear they had the same table cloths.) since I last visited it with the diving club I was a member of, some twenty-five years ago.

And so another grebe hunt came to an end, and once again the Association is indebted to Fred Binding for his hospitality and his offer of over-night accommodation, two nights in fact. Many thanks Fred, for setting up the weekend.