by Wendy Killoran

Wind whistles again through the treetops on this August day, a relentless reminder that I’m a sea kayaker practising patience and respect for the sea. A tempestuous sea rolls wave after strong, white-capping wave in a spray of unfurled power onto the gravel beach. It is a land day. Again the sea is too omnipotent. I am chomping at the bit to complete this journey with 165 kilometres remaining to be paddled.

How does one summarize a 3000-kilometre circumnavigation of the Rock (Newfoundland’s moniker)? The experience has transcended deep into the core of my being.

The solitude on the water has been profound. With the exception of the fishermen mainly focused on their frenzied work and not some anomalous paddler, I have only met birds, whales, fish and porpoises on this vast aqueous realm. I have found it unbelievable in this paddling paradise, that I have not met a single kayaker on the water unexpectedly, after more than three months of paddling. I have tried to comprehend why.

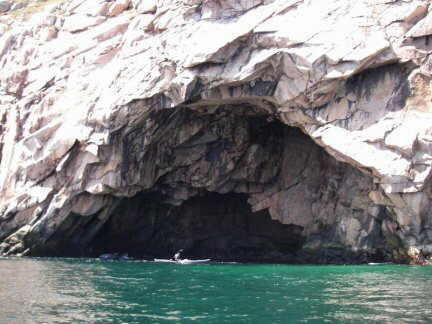

Is it because I have paddled amongst cliffs and ledges fully exposed to the powers of the sea, offering no respite and protection for dozens of kilometres? Paddling ’round the Rock has given me a genuine appreciation for this unique place, jutting out into the vast North Atlantic Ocean, on the eastern edge of Canada.

The challenges have come at me fast and furious. With lengthy paddling days allowing no possibility for safe landings and often as many as eight hours of confinement in my cockpit, I have learned to endure discomfort and to accept these lengthy days as an opportunity to extend my own personal limits. Hour after hour, I have paddled with a rhythmic cadence along rock cliffs that tumble into the ocean like a fortress’s protective walls. I paddled with urgency, never quite relaxed, always aware that the conditions could change in the wink of an eye from a placid place of contemplation to a fury of unrelenting power, challenging my skills and strength. I gazed in constant wonder at the stark beauty of the towering mountains and the ledges of limestone, always anxious that the whisper of wind rippling the water could become a full blast gale. More than once I found myself paddling with all my strength and courage to reach the sanctuary of a cove or harbour. Always I arrived relieved and humbled. It often felt like I played a risky game of Russian roulette, and as the journey progressed, I found it increasingly difficult to muster more strength, courage and motivation to risk another day upon the unpredictable sea.

The weather conditions have been as vast as the new vocabulary I have learnt from the Newfoundlanders I have had the opportunity to meet. I have been blessed with calm, comfortable, sunny days, but I have also paddled through pouring rain that stings the flesh with its cold, needle-like assault, covering the water in bouncing pop-corn kernels. I hunkered down, bent far forward, head buried in my Gore-Tex hood, relishing the downpour showering everything it fell upon. I have paddled in fog so utterly dense, that I could not see ten metres beyond the kayak’s bow, ensconced in a blind world with a 360 degree view of water far from land, sometimes for over an hour. One particular time in Exploits Bay, hopping from island to island spread at least five kilometres apart, not even a hint of wind blew. I was in a silent world of extremely limited visibility. I use only topographic map and compass to navigate, but began to appreciate the merits of GPS. I learned to trust my navigational skills and to remain confident where it was easy to become disoriented. Confidence is mandatory when paddling ’round the Rock. I often experienced idyllic paddling conditions throughout the day only to be challenged by a strong blast of wind as fatigue was setting in. Once, I watched a line of white approach me across the Strait of Belle Isle. Within minutes, I felt like I was sitting on a bucking horse in a rodeo, paddling the last two kilometres across Pistolet Bay for all I was worth; humbled yet again when I set foot ashore in Cook’s Harbour near the top of the Northern Peninsula.

The excitement and newness of an expedition eventually wears away to the reality of the monotony and hardships faced on a daily basis. And on a solo expedition, as the kilometres flowed in the wake of my kayak, I felt the loneliness. Along the south shore, I’d paddled with a new friend, Freya Hoffmeister, an accomplished, exuberant German paddler, who less than a month later became Greenlandic champion in Sisimiut, Greenland. We shared laughs, challenges and each other’s companionship, but when she left to return home, I continued paddling solo, first admittedly with a sense of apprehension, then with growing confidence, and finally with a feeling of loneliness as the weeks flowed into months. A friend provides support, emotionally and physically. I learned the value of a compatible paddling partner and was recognizing the magnitude of my journey. Yet paddling solo literally opened doors when I stepped ashore.

As the journey progressed, I felt the fatigue. To paddle eight hours or more a day, day after day, took its toll. It could be compared to running a marathon (40 kilometres), five days or more a week. It became increasingly difficult to rise with the sun at five or six o’clock in the morning, in order to take advantage of the calmer water conditions when making long crossing. I felt not only the physical fatigue, but also the mental fatigue. To continuously face the uncertainty of each day requires an unlimited sense of self-motivation. I always wondered about the wind, possible landing places, where to end my day and who I would meet. And though there was certainty in the routine of the paddling day, there were always these elements of uncertainty playing on my psyche. As the weeks flowed into months, it became easier to rest and sleep solidly.

I had given myself four months, from early May to late August, to achieve my primary goal, which was to circumnavigate Newfoundland by kayak. I’d estimated approximately 90 paddling days averaging about 30 kilometres a day. This afforded me rest days if necessary and wind delays, another challenge I often faced. I was windbound on the lengthy sweep of a beach at Lumsden for six days due to strong, gusting, offshore winds. I also faced the daily challenge of finding a safe and suitable landing site. Newfoundland is called the Rock for obvious reasons; beaches are as rare as Joey Smallwood aficionados. Most landing sites are cobble beaches. I learned to accept the fact that my kayak’s hull would show some signs of wear and tear. And although I chose to circumnavigate Newfoundland because of its stark beauty, I’d also selected it because of the Newfoundlanders’ reputation for being genuinely hospitable. I felt safe here, but always wondered whom I’d meet. I learned to trust my instinct and intuition. I enjoyed the balance of natural beauty and scattered outport communities. Days of solitude were balanced with evenings of social interaction.

I felt I was always hurrying as soon as I launched. If the water was calm, I wondered how long it would stay calm. If there were wind and waves, I wondered if the wind would shift against me, or if it would increase in strength, with building waves. Weather predictions were as unreliable as the weather itself! This sense of urgency accompanied me constantly. I tried to enjoy myself, but often when I explored a cave or beached the kayak in an inviting cove, I felt the wind would admonish my disregard to its potential presence and power. I learned to live in the moment as much as possible, to enjoy each moment for what it was, whether exploratory, rewarding, fearful or challenging.

With long stretches of inhospitable shoreline for landing, and sudden wind changes, many times I was challenged by large waves. I prefer tailwinds, but when waves become too big and steep, I found that I was faced with balancing the kayak by bracing rather than focusing on forward propulsion. Swells, no matter their size, I find soothing and hypnotic. Paddling in Placentia Bay towards Merasheen Island, I had literally hills of water rolling beneath me in my favour, sending the entire horizon askew. It was exhilarating. Now I truly felt what sea kayaking was like on the Atlantic Ocean.

But hardship and challenges were balanced with rewards. I do believe that the greater the risk, the greater the reward. When things come easily in life, what is the purpose? How does one grow?

Beyond the natural beauty of Newfoundland, the genuine sincerity and hospitality of the people has been remarkable. Arriving from the sea by kayak, a boat that Kenneth Tulk from Aspen Cove would “not paddle across a bowl of soup,” has afforded me the opportunity to enter the homes and lives of countless Newfoundlanders. I have heard their stories of hardship, of the collapse of the cod fishery and the 1992 cod moratorium, of young people leaving to seek employment on the mainland, leaving an aging population in shrinking communities. I can only wonder at the implications and try to fathom the face of Newfoundland a decade from now. Will their enduring spirit live on or is the social fabric of Newfoundland in an uncontrollable decline? Only time will tell.

Invitations for supper or a bed came frequently. One of my goals was to meet the people of Newfoundland. Thus, I always accepted their support and hospitality graciously. Day by day, week by week, I listened to their stories. Usually I met older couples, whose grown children had left Newfoundland because of the grim prospect for employment in their home province. It was sad to hear this repeatedly. Families are closely knit here, with strong family ties, only to be torn apart by the economics of the times. Will the sea beckon this generation of youth to return once their bank accounts are bulging? And though I met a multitude of extraordinary people, it was always as brief interludes, just barely getting to know them and then moving on to the next brief encounter. But I embraced these opportunities for connecting with the people from the Rock. They enriched my experience beyond anything I’d dared to dream possible. Their friendship, kindness, hospitality, sincerity and altruism will be within me forever. It made a solitary journey an undeniably rewarding experience, brushing away the arduous, long days on water with the comfort of warm, homemade quilts on land.

By accepting invitations from caring people, I was able to experience a culinary adventure away from my cooked noodles, and be immersed in their culture completely. I ate freshly boiled and fried cod and halibut, cod tongues, scallops, lobster, and snow crabs. I tasted the gamey flavour of stewed moose meat and the tart flavour of partridgeberry jam and pie. I ate freshly made bakeapple jam, hot off the stove. I ate staples such as fish and brewis and tried local beer, my taste buds and calorie-hungry body amply rewarded. I sat by the warmth of large kitchen stoves. I laughed and cried with these people and felt welcome and cared for. I felt like a traveller welcomed briefly into their lives rather than a tourist passing through. I felt privileged and honoured to share so intimately in their daily lives.

By visiting outport communities, I was visiting Newfoundland well off the beaten track. I was immersed in a simple lifestyle, where family, friends and seafarers are the top priorities, where materialistic possessions and mortgages are unnecessary, where food is harvested from the sea by fishing and from the land by hunting and gathering. And for the most part, these people are happy with their uncomplicated, slower-paced, low-stress lifestyle. I was rewarded with a glimpse into a lifestyle unavailable in the large cities of this nation.

Being on the water and in small outport communities for an extended period of time, I was able to pursue the simple pleasures in life that provide great joy. Scouring beaches for stones and weathered glass is always a welcome diversion. Gazing at the ever-changing texture, colour, motion and sound of water reaches deep into my soul, a therapeutic and necessary pleasure. Staying in the present moment, absorbing my surroundings, observing the sky and the vastness surrounding me is something I’m denied in my busy city life. Watching the alpenglow on mountains, listening to birds screech or sing, smelling wild roses and the tundra baking in the sun, provides a cornucopia of seasations. I gulp it in.

This extended journey has helped me reach for new personal limits and helped me grow as a person, extending the boundaries of my comfort zone. To succeed is to grow, but to not try is to never know. To cope with arduous paddling and its plethora of challenges, I have needed to remain confident, creative and spontaneous, and to apply good judgement. Many frown on solo paddling, but by paddling solo, I am accountable for my own actions. It has certainly helped me to choose to be cautious; there is little margin for error regarding arrogance and stupidity. I felt self-empowered.

Hoodoo

And though I crave solitude, I am not a solitary person. And thus the journey evolved from a shared experience with Freya Hoffmeister along the south shore to a solo experience thereafter, visiting outport communities at the end of each paddling day. Solitude provides time for reflection and contemplation. It provides valuable time spent with myself. It allows me time to meet my personal needs. Everyone should experience solitude, now that our lives have become so hurried, complicated and demanding.

I am most astonished by the many serendipitous moments on this journey. The flow, evolution and connectedness of this journey have left me gaping in awe and wonder. I am a staunch believer that everything happens for a reason, and am certain that with time, the physical journey will answer many unresolved questions of my inner journey. Ironically, Graham Oliver from Kippens remarked to his friend Dan Rumbolt in Stephenville at 2:00 p.m. on August 4, that he thought that the kayak lady he’d seen on the CBC interview should be near Stephenville according to his calculations. Precisely one hour later, I was knocking on Dan’s door. Unbelievable? Destiny? What can I say? It was as though he was expecting my arrival. Some things are simply inexplicable.

Throughout this extraordinary journey, I have learned to embrace life. I have discovered that the people are endearing, the landscape is vast and starkly beautiful, the ocean is unforgiving, and that Newfoundland, the Rock, is not only a special place for innumerable reasons, but also holds a special place in my heart. To paddle ’round the Rock is a journey beyond comparison.

Wendy would like to thank her supporters and sponsors, in particular Kokatat and Wenonah-Current Designs, for their generosity.

She wrote and submitted this article while windbound near the end of her journey. You can still (not any more, ed.) read her day-by-day on-line account of the trip at ‘Round the Rock.