by Wendy Killoran

Labrador is a land of superlatives. It is a land that truly can awaken your heart and soul as the Newfoundland and Labrador tourism slogan promotes. Its stark beauty betrays the hard realities that hardy individuals endure in this land of vast natural splendor. I’d come to Labrador to paddle with whales and icebergs. I’d come to experience Labrador both naturally and culturally. I would not go home disappointed.

Two days of travelling, five flights and ten stops later I had arrived in Cartwright, Labrador, but without my luggage. I spent two days awaiting both the arrival of my camping gear and for the gale force winds to abate. A warm-up paddle on my second day in this nondescript, unkempt town of about 800 was aborted as fierce winds pummelled our small group into Cartwright’s harbour. Ironically, the land would not let me easily commence my paddling journey yet the beauty was astounding as a vivid rainbow swept across a stormy sky.

During my wind bound days I explored the community of Cartwright on foot. It curves around a sheltered bay and is connected to the rest of the world by boat and plane. This is changing as I write, as a coastal roadway is currently under construction connecting Red Bay, site of an early Basque whaling station, to Cartwright. It is predicted that in three more years the road will connect with Happy Valley/Goose Bay which connects with the Trans Labrador Highway, referred to as the Freedom Road by locals. I walked past the Cartwright Medical Clinic, built on the site of the original Grenfell Mission. Dr. Wilfred Grenfell established a mission in St. Anthony, Newfoundland, in 1890 and served the isolated communities in northern Newfoundland and Labrador. Cartwright, at the mouth of Sandwich Bay, was named after George Cartwright, an 18th century merchant and adventurer who spent 16 years in the wilds of Labrador. It is now one of the service centres along the Labrador coast served by the ferries M.S. Bond and the M.V. Northern Ranger. Small, wooden boxy houses border the dusty, rutted gravel road which curves around a small part of Sandwich Bay. Komatiks and ski-doos lay idle, awaiting another cold winter season.

Fortunately I was no longer idly awaiting to paddle. On my third day in Cartwright, we slipped our loaded kayaks into Favourite Tickle in Sandwich Bay, ready to explore the vicinity at the crack of dawn. I was paddling with Pete Barrett, her son Tom Barrett, both from Newfoundland and Tricia Kinsey, a nurse in Cartwright who was originally from Australia. I was thankfully out of my hotel room, which was adorned with glossy blue walls, and kitsch curtains and quilts resembling the Labrador flag. The bottom blue stripe represents the waterways, the green the land and the white band on top, the snow. The spruce twig, common to all regions of Labrador, represents the people of Labrador; the Innu, the Inuit, and the European descendants. Labradorians are proud of their heritage. I was simply happy to be paddling, ready to have my senses tantalized as only nature can do.

Paddling under sunny, calm skies, our four kayaks left Favorite Tickle. (A tickle is the Newfoundland word for a passage of water between land.) Wooded, low, rounded humps of islands appeared. A slight tail wind gently urged us to make a six and a half kilometre crossing to Huntingdon Island easily with the aid of the falling tide. Pete, a sailing aficionado, tied her homemade neon-red nylon sail to her paddle and let the wind work to her advantage. The power of the ocean was noticeable immediately as I usually paddle the Great Lakes. The water was a dark, impenetrable colour. I was on the water but couldn’t see through the water. Scattered summer homes, weather worn but functional, occupied sheltered grassy shorelines. I was surprised at the number of summer homes, but as recently as two to three decades ago locals lived in these places to fish during the summer months.

Near Indian Head on Huntingdon Island, we disembarked for the first time on the trip. I was introduced to the “Wendy Wiggle”, a drama of squirming to extricate myself from my newly purchased dry suit, a worth while investment when paddling the cold waters of the Labrador Sea which never warm over 4 degrees Celsius. I emerged looking like Cousin It from the Adams Family, as Tom commented. I was in olfactory heaven with the heady scent of tundra carpet baking in the sunshine.

At Old Man’s Cove on Huntingdon Island, I roamed amongst a couple of summer houses and then enjoyed my Labradorian dinner (at home my lunch) of flummies fried in the grease of bacon. Flummies, also referred to as river cakes or stove cakes, became a staple of my diet and are simply a mixture of flour, baking powder, salt and water. There’s even a group of Labradorian musicians called The Flummies!

The tide had ebbed and we carried our kayaks about twenty metres to water’s edge to resume paddling. We made a three-kilometre crossing to Newfoundland Island (not the large provincial island!) also known as Prisoner Island, as a man who had killed a fellow sailor on a schooner had been left to fend for himself, completely isolated, for the duration of a summer on this island. To reach Newfoundland Island, we group sailed part of the way, all four kayaks in tight formation with a tarp as our sail.

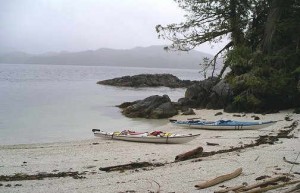

At Dumpling Harbour, we beached our colourful flotilla on a sandy strip festooned with marvellous streaked metamorphic rocks filled with burgundy garnets, some as large as two centimetres in diameter. We walked over seaweed that snapped and crackled to Tricia’s summer house, an old, grey two storey fisherman’s salt shed on stilts. The upstairs, with large picture windows, afforded us a panoramic view of Dumpling Island across the tickle with a dispersion of summer homes on land void of trees.

I wandered on foot westwards and discovered a gnawed caribou antler, a supplementary calcium source for rodents. Orange lichen splotches painted the visually appealing bedrock. As we returned to the kayaks, a dramatic, threatening sky loomed in the west. Soon spatters of rain plunked little radiating circles on the inky black water but it was short-lived. The wind had picked up and my kayak bobbed over some playful waves.

Landing at Pigeon Cove, on Newfoundland Island, we set up our tents on a height of land behind Gordon and Barbara’s well kept home. Gordon and Barbara were relatives of Pete; with a total Labrador population of only 30,000 most Labradorians know or are somehow related to just about everyone. We were invited to make ourselves at home while the owners went fishing for sea trout and salmon.

I climbed a nearby hill with Tricia, over a carpet of Arctic vegetation, partridge berries, blackberries, bakeapple berries, mosses, and grasses, to be rewarded with an expansive view to the north of cathedral icebergs drifting southwards in the Labrador Current. Small, stunted spruce trees hunkered in depressions, some merely thirty centimetres high and probably over one hundred years old.

Supper (my dinner at home) consisted of baked beans sweetened with molasses and brown sugar, and sweet and sour moose meatballs, a true cultural gastronomic adventure, cooked over a wood stove. Another ramble over the hilly tundra afforded me another splendorous view of the parade of icebergs and brought me to a patch of snow at sea level in July!

Listening to the murmuring wind on the ocean in the distance and a chorus of songbirds, sleep came easily as I was camped on the soft, spongy tundra. The sun still rested in the western sky. A few mosquitoes hovered around my tent but weren’t present in fierce, voracious numbers.

A curious harp seal peered at me from Pigeon Cove in the morning as we departed in calm, glorious weather to Pack’s Harbour on Hamilton Island. Hardly a soul was there. In years past, bustling fishing activity would have filled the harbour.

We paddled towards Tinker Island and the open, exposed ocean with gentle, rolling swells placidly rocked our kayaks. A galaxy of millions of tiny transparent jellyfish pulsated in the dark water below the hull of my kayak. I was mesmerized to watch this magical world beneath me. Northwards, like tiny specks, colossal icebergs floated southwards, born in Greenland and melted by the time they reach the southern shores of Newfoundland.

We paddled along the south shore of Horse Chops Island, covered in wooded hills, and very flat and mesa-like in appearance. Dead calm waters intoxicated me as I paddled and noticed shafts of light pierce the water, penetrating and converging deep below. These light shafts travelled through the jellyfish, illuminating them in iridescent sparkles of intense, brilliant colour. I couldn’t believe the profusion of life pulsating below me.

This beach excited the Vikings enough to be recorded in their epic sagas as they travelled to the present day World Heritage Site at L’Anse Aux Meadows at the northern tip of Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula. Apparently natives found this area conducive for habitation as the astounding depressions beyond the beach, filled with curious cobble-like paving, are replete with archaeological artifacts. A team of archaeologists was arriving within the month to study the area, which will become the eastern extremity of the proposed Mealy Mountains National Park. Hopefully the proposed logging of the oldest boreal forest in the world north of the proposed park boundary will be aborted. How can anyone support the destruction of such a natural treasure?

A lengthy walk along the strand occupied me once we arrived on this sea grass fringed wonder in this predominantly rocky landscape. Fog shrouded Horse Chops Island in tendrils over the hilly tops and wisps of fog raced over the sand on the strand. Colus, mussel, and clamshells were strewn over the beach. Up on the rim of the embankment, dead, silver bleached spruce trees sculpted by the forces of nature stood naked and exposed. Bear scats, purplish in hue and filled with berry skins and pits, were plopped in numerous spots and trails of cub prints and caribou tracks were freshly imprinted in the sand. The sandy embankment gave way to dark brown sandstone, no longer sand but brittle to the touch, not quite yet stone. The beach had me spellbound but it was time to return to camp for another filling feast.

We enjoyed the warmth of a campfire and folkloric tales and stories of how life used to be, as loons swam close to shore. Pete has a vivid imagination and captivated me with her ghost yarns of the area.

In the dim light of a foggy morning, our group wandered through the intoxicating tundra landscape, pockmarked with sandy depressions and stone-filled basins. Had glacial retreat caused this unique landscape? We puzzled over our find and then paddled through the lifting fog to Sandy Point, the southern part of the Porcupine Strand. Here we explored a small cemetery situated in a grassy meadow on the very tip of the peninsula. The graveyard was testimony to the Spanish flu epidemic brought on supply ships which had decimated the Labrador population in 1918, killing approximately one third of the entire population and devastating entire families. Headstones indicated that several family members had died within days of each other in the late autumn of 1918 here at North River.

I wandered the western beach of the point and noticed very fresh bear prints once again. Our group paddled up the North River, banks enclosed by dense black spruce forests. The day had warmed up considerably, enticing Tom and me to loll in the water off a sandy shoal in our dry suits. How refreshing!

We set up camp on the summer house lawn of Bill and Joyce, along the north bank of the North River. A black bear ambled along the shore as we arrived. Fresh sea trout was caught and fried to complement our supper of fishermen’s brewis; a hearty meal of salt fish, hard bread (soaked all day in water) and smashed potatoes, another traditional Labradorian meal. The evening was spent visiting Doris, a local woman who was very hospitable and taught me more about life in Labrador. Cell phones are nonexistent in this part of the world and I listened to Doris take a radio call, along with the rest of Labrador’s coastal residents!

Following a flummy breakfast, filled with scraps of meat, which in years gone by would have been game meat like caribou or moose, we paddled under grey, somber skies which made the undulating Mealy Mountains look drab and dark. The cold convinced me to don neoprene gloves and a fleece headband, which quickly changed to my bright yellow homemade sou’wester hat as a deluge of rain was released from the sullen sky. The lengthy downpour was entrancing. Each drop of rain bounced like popcorn popping as it smacked the glassy smooth grey water in Sandwich Bay. Each drop sent a small circle of concentric rings radiating from the droplet that appeared momentarily like a floating glass bead before it mixed with the salt water.

We circumnavigated Diver Island and returned to Cartwright where the outgoing tide pulled us to our take-out location. A garden of sea kelp pulsated in the water off Shermoks Point. At night, in the Barretts’ shabin (cabin-shack), I enjoyed George Barrett’s resonating voice singing Labradorian tunes, as he played his classical guitar around the susurrus purring of the propane heater.

The second week of paddling took me eastward from Cartwright. A cold, brooding day awaited. My breath condensed as I exhaled. A damp mist permeated everything and the breeze had a cold bite to it, coming from the cold Labrador Current. I wore two or three layers of fleece to stay warm. Apparently it was abnormally cold while I visited Labrador. The benefit of such cold conditions was the almost complete absence of black flies and mosquitoes, which can be quite the nuisance when present in droves during July and August.

Pete, Tom and I paddled to Cartwright Island, an eight-hour paddle. At Venison Head, we stopped to refuel our bodies. Rounding Venison Head, marked by inuksuit, a seal surfaced a few metres in front of Pete’s kayak. East of Curlew Head, two icebergs appeared in the distance, one resembling a cat with its front legs stretched out. A few puffins bobbed on the calm, placidly rolling ocean. A silver sheet of entrancing water undulated hypnotically. It was a euphoric paddle, far from land which was barren tundra. In Blackguard Bay our three kayaks, side by side, lifted and dropped on the swells like a child’s slinky. A guillemot with frantic wing movements, a white circle on top of each wing and red feet pointed back, circled us numerous times.

We camped in a sheltered cove midway up the western shore of Cartwright Island. Ferried by long boat, a couple from Newfoundland, Kelly and Alec Feltham, joined our group. A wind buffeted my tent walls, set with an expansive view. Following supper, I ventured to the northern tip of the island where I found an enormous stone ruin. Was it Cartwright’s house or was it pre-Cartwright as the lichen on the massive rocks would suggest? A raised beach was near the ruin, flat shingle stones encrusted fully by extensive, dark lichens. While walking, the cold wind reminded me of the harsh realities of this stark, unforgiving land. The silence and space around me were mind boggling. Solitude was easy to find.

The wind next day blew from the southeast and the waves were quite choppy once we were out of the lee of Cartwright Island. We stopped for dinner at Toomie Point and here we became wind bound as the relentless wind increased in velocity. A mussel bake ensued and we found minuscule pearls in some of the mussels Alec and Tom had gathered. Rain came and went all day. After dinner, we walked up the hill and found what appeared to be a rock ruin in a circular shape, rocks covered thickly by lichen. Who knows what it was or who built it? The land contains so many silent, puzzling secrets.

A southeast wind continued to blow the next day, and vigorous paddling into choppy waves that sent the bow of my kayak plunging in the troughs got us across Curlew Harbour. With my sail raised on my paddle, I surged forward as waves and wind powerfully propelled my kayak. At this point, near the western tip of Curlew Head, a pod of four Atlantic orca whales surfaced, spouting large plumes of water and displaying enormous black, curved dorsal fins. They were about 150 metres off my port bow but it was nevertheless a powerful moment.

At Curlew Head we settled in Sam Holwell’s summer house and stoked the wood stove to dry out our drenched gear and clothing. Colourful paddling paraphernalia festooned the panelled walls and soon the seaside window steamed up from the humidity. Wind bound again, Kelly, Alec and myself went adventuring by foot. I had remarked that it would be exciting to make a great find. Remarkably, we did! After traversing tundra and descending and ascending a gorge, and climbing a gently sloped hill, we came across a circle of stones laid like tiles, again fully covered by lichen. Nearby, we chanced upon a community of building foundations in ruin and covered in bunchberry vegetation, looking identical in nature to the unexcavated ruins at L’Anse Aux Meadows. Had we made an archaeological discovery? No locals had spoken of the site and it was not indicated on the maps produced by Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine Ingstad, renowned archaeologists credited with the L’Anse Aux Meadows Viking ruin discovery. Had the Vikings passed by here from the Wunderstrand to L’Anse Aux Meadows? Quite possibly!

Returning toward Cartwright, the wind at our backs, was now in our favour. What had taken us two days of tortuous paddling to attain, we regained upon our return in one hour! We paddled next to a patch of snow. Eider ducks with their fluffy ducklings often swam nearby. We sighted razorbills, murres, and black-backed gulls often. A lone minke whale silently surfaced and disappeared next to Pete’s kayak in a fluid, fleeting moment.

East of Hare Island, Tom and I paddled to two “bergy bits”, small icebergs which were grounded. Thunderous waves pounded and smashed the sculpted ice, perhaps thousands of years old. At times glimpses of sun peeked from the grey cloud cover, making the berg glow and sparkle an iridescent icy blue. It was magical. The berg was open in the middle, with a tall wall with fluted columns like an organ pipe. It had made its solitary trip from Greenland and now was disappearing back to the ocean. I enjoyed the diversion.

We camped on Hare Island, a heavily forested height of land. Black spruce with dangling tufts of black “dead man’s beard” lichen dominated. While enjoying fish and brewis for supper, I once again saw a minke whale surface. We bushwhacked up the towering hill beyond our campsite, thrashing through tangles of black spruce and cushioned underfoot by mosses. Fog rolled in and I was content to return to the warm and inviting campfire.

On the final paddle to Cartwright, wind, waves and tide were all in our favour. Our kayaks surfed down the front faces of the waves. A harp seal peeked at us near Curlew Hill. My paddling adventure provided me with an opportunity to experience Labrador in a fulfilling way. My efforts were rewarded with profound and sublime landscapes. My contact with the people of Labrador endeared me to their way of life. The land of Labrador is compelling. It has awakened my heart and soul with its grandeur.